The 2023 Metro Times Fiction Issue

Edited by Nandi Comer and Casey Rocheteau.

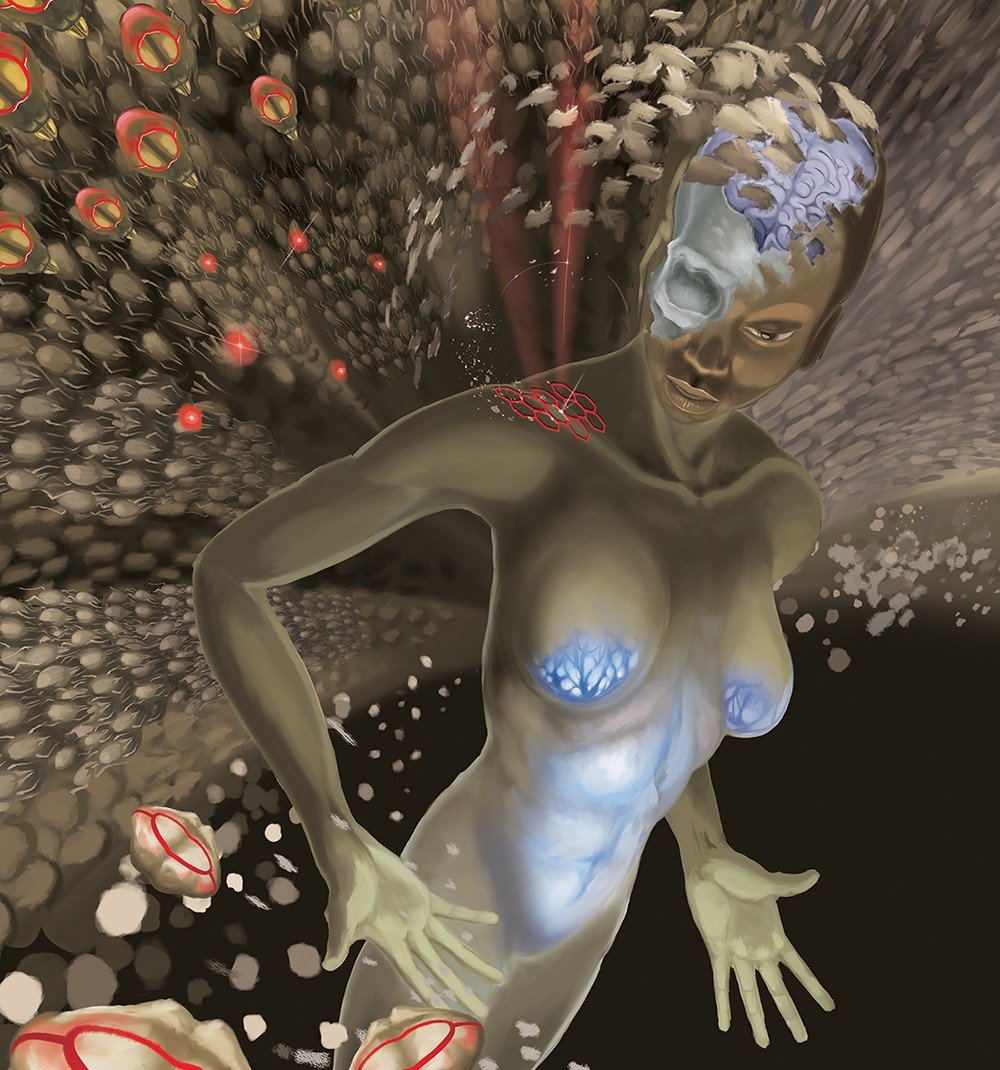

Cover art by Solomon David Johnson, “Are We Human Enough?”

Detroit is a city that speaks when entering a room. When we visit our loved ones, or are at the gas station while waiting in line to pay, or merely as we pass a stranger on the street, we acknowledge one another. When we come into a space we say “Hey, how’s it going?” or we give a head nod or the most common greeting, “What up doe?”

Whether you are a lifelong friend or a new acquaintance, we speak. We check in.

Our way of greeting is Detroit’s way of inviting each other to share space. It is the way we love each other — even strangers. It is the way we recognize a collective consciousness in a city where thousands of people, each with their individual stories, work their way through the day.

This year’s Fiction Issue contributors have created a shared space speaking to one another and acknowledging a shared experience. The pieces in this issue offer meditations on identity and grief. They relish in the celebration of ancestors, traditional practices, and healing. The way we grapple with technology and our sense of self is seen in this year’s cover art, “Are We Human Enough,” created by Solomon David Johnson, and further echoed in the poem “DETROIT BABY” when the poet by Yasmine Roukiaya meditates on desire in a tech world. In “Bearing Witness,” Carole Harris invites our eyes to witness the narrative in the layers upon layers of her quilts. She reminds us that Detroit narratives show how we believe something to be true. And in Sterling Tole’s “Get Yo Mans” I see our audacity in the eyes of the cluster of young men who are both receiving and daring the viewer to respond in any way as long as it is respectful.

Reader, included in this year’s issue are stories of joy, exploration, growth, and loss. In other words, this issue is the most Detroit greeting I’ve seen since we started producing the Fiction Issue. I invite you to enter the collective room these artists have created.

Nandi Comer

The fiction issue is a collaboration with Kresge Arts in Detroit to elevate local artists. Artist fees were provided by Kresge Arts in Detroit, a program funded by The Kresge Foundation and administered by the College for Creative Studies. Nandi Comer is this year’s editor and Casey Rocheteau the deputy editor. Solomon David Johnson is the cover artist.

La Dulzura

By Esperanza M. Cintrón

The repast was at tia’s café in Loiza, Daddy was dead

and we laughed, talked loud, drank, ate papas rellenas

arroz con pollo and made piraguas for the kids, but tio

the last of seven brothers, dragged a straight back chair

across the dirt road, his faltering eyes squinting up

at the sun as he sat and pulled a long stalk of sugar cane

out of nowhere then chewed at its tip, splintering the thick

skin as he and his brothers, now boys in short pants, bare feet

and arms filled with stalks pilfered from a nearby field bent low

slipping past the open window where abuelita sang along

with the radio a tender bolero as she sliced yucca for dinner

all grins their toes sinking into soft grasses the boys

squatted behind the house savoring the looted stalks

strong teeth tugging, splintering then spitting bark before

sucking the juicy flesh as tio savored the sweetness

the afternoon sun warming the many creases in his brown face

Esperanza M. Cintrón is the author of Shades, Detroit Love Stories and four books of poetry including Boulders which was released in January 2023.

“Ghetto Palms & Momma’s Rage”

By Vanessa Reynolds (Venusloc)

Oil on Canvas, 5’ x 4’

Vanessa Reynolds (Venusloc) is a self-taught interdisciplinary artist born and raised in Detroit.

A Nothing Year

By Morgan Mann Willis

Everyone will tell you it started with a bang. No. It was a boom.

On Thursday, September 29th back in 1998, I was walking past Mr. Orman’s house and noticed the little Japanese maple bush. Only reason I knew about them was because the day before, my girlfriend Alicia McGray took me to the little botanical garden out there in Andersonville for my birthday. Turning 19. A nothing year. It was a small place but we walked around like a couple of plant sophisticates, pointing out textures and colors until we ended up surrounded by a small forest of thick maroon Japanese maple shrubs. We were alone, the timing was perfect. I started fumbling around her bra, hoping for a little luck in the garden. From around the bushes I heard a voice saying, “Orman’s got one of those now, just put it in.”

I remember looking at a lanky sapling next to the biggest tree and vaguely registering the voice as familiar. But my mind was bloodless. Alicia leaned in and gave me the sexiest kiss. What was that? Twenty six years ago? I still remember. Right then her grandma comes around the bend and stares at us. I froze. Alicia let out a quick yelp. She was still holding the button on my jeans. There we all were. Alicia was the first to move and when she did she started swiping down the front of my pants like they were dusty. Her grandmother just stared at my feet. Head low; heavier than embarrassment. Shame.

“Alicia,” she said, saying her granddaughter’s name like they were enemies.

I turned and faced the far corner of the garden, trying to get myself together. Give them a moment. Everything around me was suddenly the most interesting thing I had ever seen. In the back corner there was a two foot hole in the dirt. A tree had been dug up, messily. I assumed it was the botanical garden’s doing. Maybe it died. I turned back around to Alicia crying and her grandmother gone. We walked to the car like we were leaving a funeral. There are certain birthdays you never forget.

So the next afternoon, I happened to be walking by Mr. Orman’s house on the way to the gas station and saw the bright, little maple tree. Naturally, I slowed down. That morning Alicia called to tell me I couldn’t see her for a while. She was sure her family already learned what happened from her grandmother. They’d all know her shame soon enough. She talked like it was murder. I couldn’t get a word in over her crying. Tough gig, I thought. Day one of being 19? Dumped. My mind ran from the lump in my throat. I thought of the hole in the garden. Was this the missing tree? It was the same kind of red. Weren’t they all? How would Mr. Orman have pulled that stunt off? My heart was thumping. I was 19. I didn’t know heartbreak — how it seizes your chest and crumples it into a little ball, like old tinfoil. Then it happened.

Thirteen of the biggest birds I had ever seen came swooping down in a perfectly straight line. So, I guess if we’re going to be accurate it wasn’t even a BOOM that started it all. It was the faint sound of those wings in flight. I almost dove down onto Mr. Orman’s driveway. Instead, I ran behind the maple and squatted down. I didn’t know what else to do.

They landed on the telephone pole right in front of me. Snowy owls — the white ones that look like hawks. That’s the other thing people keep getting wrong. No hawks swarmed Gornton. They were owls. Thirteen of them, right at dusk. Twenty-five seconds later the transformer on the pole they had all chosen exploded. That was the boom. In a split second I saw a huge orange and black bubble of fire expand and burst into smoke and flame. A few feathers went flying, I’m sorry to say. Some thinner branches on a big oak tree next to it caught fire but they fizzled. Then, pole by pole, the explosion spread. Power went out all around me. Those were the bangs. In five minutes the whole town was powerless. I stayed behind that shrub for a while. Imagine me, 19 years old, heartbroken, hiding like a kid, afraid of the dark. The lights never came back on. So I finally got up, dusted off my pants, and ran home. Later that month I saw Mr. Orman’s neighbor, Jasmine and she said yup, she saw the whole thing too and even told me that the surviving owls stayed until the next morning.

All of Gornton was down that night. The flashlights, oil lamps, headlights, whatever we had did nothing to illuminate the dark. East, west, uptown, the Union. No one had seen anything like it. Seemed like forever. Three days and some change, no power. And you know what? It started out okay. Then it went a little crazy.

We call those days, The Nights.

Morgan Mann Willis (she/they) is a storyteller whose work explores themes of memory, mundanity, and home.

Detroit Baby

By Yasmine Roukiaya

Fadia says as she plucks the stray hairs from my face

don't send texts that end up in mass graves

but every good Ghost story starts with presence

& I wear war like a favorite jacket

picture it a simple scene constructed from sprites: static & color

a screensaver selfie a dangly earring bouncing

like rush hour on 94 exporting ports &

neon-pink fuzzy handcuffs I came on to you like April,

a total fool; persistent & viridian a stick shift commitment

Behind the screens we glitched at the intersection of doom & desire

swirled like tyrian bruises under the marbled disco lights

All artificial means of connection fizzed its syrupy carbon away

the bugs thawed too early we kissed sooo deeply every sky became

a homeland painting yours & mine now are people

even a people if they are forgotten left on read?

Does my tongue crave the coney on Lafayette

because it is colonized? My google search only shows

pictures of Belle Isle sunny-side up, the two time zones back home,

Casper the friendly ghost & his mugshot uncles.

The albatross is born in the sky flies 20 years straight

without missing anybody my Detroit baby Habibi

with brows on fleek what I’m trying to say is

only ALLAH gets the last laugh & I’m so very sad you

had to meet me at a haunting time like this.

Yasmine Roukiaya is a Lebanese/Appalachian/American lyricist, fictionist, and performing poetess living in-between hyphens, genres, and political streams of consciousness.

“The Titanz”

By Mieyoshi Ragernoir

Oil on canvas with digital effects

Mieyoshi Ragernoir is a painter, art educator, and mixed media artist from Harlem, NY; she creates celebratory paintings archiving the connections of people, heritage, and joy; predominantly portraits highlighting the radiance of Black femininity.

Aretha Franklin,

Rock Steady for The Queen of Soul

(1942-2018)

By Melba Joyce Boyd

“Aretha sang the way black folks sing

when they leave themselves alone.”

— Ray Charles

God lifted your regal voice,

invoking your father’s

seamless faith and mission,

marching with Martin,

to sing for our King,

for his vision,

for his dream.

“Mary, don’t you weep,

Pharaoh’s army got drowned”

Your songs soar with angels,

strengthen our resolve,

demand RESPECT

like a Natural Woman,

to THINK, to Do Right

despite racial strife

or some lowdown man,

inflicting endless grief

on a woman’s pain,

cause

“Ain’t no way,

Ain’t no way,

for me to love you.”

Hailing from

New Bethel Baptist,

your gospels bring

healing to sorrow,

subvert suffering,

and inspire choirs,

preachers in pulpits,

and even the Pope.

“Got to find me

an angel.”

Your rhythm and blues

are liberation anthems,

Bridges Over Troubled Waters,

elevating inaugurations for

Presidents Clinton

and Obama,

crowning your

legacy Gold

with the Freedom

Medal of Honor.

“What it is,

What it is,

What it is.”

Amazing grace, how

sweet is your sound

born in Memphis,

raised up in Detroit city,

reaching Spanish Harlem,

with spiritual reverberations

scaling a nation’s blues,

revolutionizing American

music, blessing an

entire world

making us whole.

“What it is,

What it is,

What it is.”

Sista Re’s gone home.

“Mary, don’t you weep,

Martha, don’t you moan”

Rock Steady, baby.

Rock Steady for

Aretha Franklin,

the Queen of Soul.

Melba Joyce Boyd is an award-winning author of nine of books of poetry, two biographies, editor of two poetry anthologies, two documentary films, and is the 2023 Kresge Eminent Artist.

“Bearing Witness”

By Carole Harris

53” x 42” Commercially printed cottons, acrylic paint on muslin, cotton battingand thread.

Carole Harris is a nationally recognized fiber artist and 2015 Kresge Fellow, whose abstract compositions expand on the basic concepts of quilt making, while telling the stories of time, memory and place through the use of densely layered textiles, stitchery, and mixed media.

When We Were Close

a short play

By Shawntai Brown

CHARACTERS:

LAJOY - a lesbian stud

STRAIGHTIANA & FRIENDS - feminine Black women

SETTING:

Detroit, a straight club in a time when lesbian bars are extinct.

Club lights flicker. Bad

music plays. LAJOY stirs

her drink. She is alone; the

bar is crowded.

STRAIGHTIANA enters,

sets an empty glass down

in the tight space next to

LAJOY, waits.

LAJOY

(After a moment.)

Kill the DJ, right? Cain’t nobody dance to this!

STRAGHTIANA ignores

LAJOY. Or doesn’t hear

her?

LAJOY

(Tapping STRAIGHTIANA’s shoulder.)

I said—

STRAIGHTIANA whips her

shoulder out of reach,

looks LAJOY up and

down.

LAJOY

I wasn’t trying to—

STRAIGHTIANA turns her

back.

Just making conversation...

STRAIGHTIANA snatches

her refreshed drink,

dancefloor bound. LAJOYA

stands, grabs her hand.

STRAIGHTIANA freezes.

A spotlight falls around

them. Remaining lights

dim to black.

LAJOYA

Remember, we used to be girls?

Not me and you, specifically. Me and your

kind.

STRAIGHTIANA

unfreezes, retreating to

FRIENDS who appear

under a hazy spotlight.

They touch constantly:

dancing, fixing hair,

makeup, hugging for

photos.

Back when you were tomboy-era-Aaliyah

and I was Da Brat Tat Tat, posing back-to-back

in front of an airbrushed skyline.

Now, I can’t even get close.

Which is funny to me, because one thing

we do as women is touch.

Constantly.

Like it’s necessary.

When I see a string of women carving

through the club like a moving Wall

of China, I see us not-so-long ago: finger-

linked or with our palm at the small of the

next one’s back, caravanning. Our

borderless skin — a whole spell.

Remember, we’d form covens of vibrating

hips? And when we was really feelin’ the

music, it was ass to pelvis! Palm into

shoulder of your bestie — to steady

yourself — while you were giving whatever

nigga’ was behind you That Work!

I was your shoulder.

Unwilling to let a nigga grind on me, but if

you wanted bounce that ass — I was your

support staff.

Remember? Piling together, laughing at

the TV: three sets of thighs squished

together on the sofa, and my body

sprawled across.

Remember how no one flinched at my

touch?

You flinch now.

See my men’s-section clothing; second

guess why I’m here. Like I’m not dodging

their gaze, too.

LAJOY approaches

STRAIGHTIANA &

FRIENDS.

Remember our touch as platonic love

offerings? Taking braids down in class.

Oiled fingers on a dry scalp. Sharing

chapstick — no danger predetermined on

my lips.

I want that back.

To fix your hair — no flirtation assumed.

LAJOY moves closer.

To sit closer to you at the bar and talk

about how bad the DJ is.

Even closer.

Could you hear me? If I wore heels? Short-

shorts with my titties elevated and

revealed?

Could you remember me then, as one of

your girls?

Me as me — as us;

LAJOY, now nearly in their spotlight.

and not another nigga you ain’t got time for at the club.

LAJOY’s spotlight cuts out,

disappearing her.

STRAIGHTIANA &

FRIENDS remain lit,

posing for a photo. Lights

flash.

Blackout.

- END -

Shawntai Brown is a Detroit playwright, poet, teaching artist, and co-host of Woman Crush Everyday, a webshow for fans of Black queer women-centered media.

“Within the Garden: Self”

By Miranda Kyle

“My work reflects the stigmatized ideals placed on black individuals, but flipping it by giving them representation from their perspectives.” —Miranda Kyle

The Ocean Deserves a Song

By Jazmine Cooper

My mother is dead. I know this because she appears in my dream, baking a cheesecake in a kitchen I know but do not recognize, to tell me the hurt I have felt is a pool that I must submerge myself in. Why would I want to do that? Because time is not a salve, but a weapon and my time is almost up. There are too many dead calling my name, too many.

I learned this way before I was born in water. I knew this before I learned about the sinking.

I have sunk to the bottom of this pool. I have heard the whispers of my ancestors speak time into my name.

My name, my name.

When I awake, I am late for work the last time I am allowed to be late. I am going nowhere, my body cemented in my sheets. My first thought: I can’t afford this. I can’t afford… this. I cannot help but stare at the white, digital numbers on my phone. My world is an ocean, and I am sinking. This reminds me of my lover’s grasp and its forbidden clutch, but this has nothing to do with it. This is what the ocean does to the mind after the body has dissolved. This is what the tangling does to ones who believe they are not a mess. I am used to the sinking, but the ocean still swallows.

I get the call that I am fired, and my boss decides to lecture me about my usage of freedom. Do not lecture me about my freedom. What is freedom when the mind is hostage to itself? My mind knows everything about chains.

My body knows everything about chains. Even loose metal holds a grip on tender wrists for generations and generations.

I roll over to the window, where the blinds are closed shut. The dark is a swallow, whole and choking. This is not how I am supposed to be. I remember many things like why I am so alone. I am in a city I never knew, where the only patrons of my existence are my ancestors. Do they know why I am so alone? Should I ask them?

Should I talk to god? What is poor design to the divine?

My room is dark. Instead of opening the blinds, I light candles as though the small satisfaction will mend this sinking. I think of my lover’s hands and the crevices its caresses do not touch. They appear at my door knocking, knowing that I am here because this is a convenient time for them. When I don’t answer, I hear them become angry. My phone rings and rings, and they call me call me call me.

When I open the door, they are wanting, and I am too vulnerable to resist. But even when we are together, they don’t say my name.

To not think, I decide to dream. I dream of my flesh falling loosely around my ankles, my flesh becoming more than water, ebbing and flowing like a wave in a calm ocean. I am one with what should heal me, but for that to happen, I must become the healing. I do not know what this means or how the healing should be, yet I am here.

I’m awake. The sky is dark and there is air in my lungs. I breathe deeply.

My father calls me to tell me what I already know, and I hesitate to tell him that I saw her in a dream, radiant, and happy. My lover must go, and I tell them to not come back. I tell them the reason is they never knew my name, the name I have breathed life into. I don’t care they are confused, but I need this more than I need them. I need the wholeness of my name to fill my mouth until I am choking, to let me know that I am still here and my heart beats and beats and beats until it will pass onto another name.

When I look at the blue-black sky, my ancestors scream my name from the deep. I am still here. I am.

Jazmine Cooper is an MFA student at Antioch Los Angeles and lives in Detroit.

“Preface to Violence”

By Kikko Paradela

2022, Poster, Archival inkjet print, 42” x 68”

Kikko Paradela is a Filipino-American, Detroit-based artist, an independent designer, and researcher.

Echomaking: Corvid, Double

By Kristen Gallerneaux

There are four people sitting around a kitchen table in a house alongside the Snye — the Chenail Ecarté — the edgeland of Bkejwanong Territory, “where the waters divide.” From the outside, looking in, the room glows orange. Light diffracts through a wicker lamp swagged on a gold chain over a hefty wood table with mismatched chairs and unpainted chipboard-panel walls. Jars of expired spices, family photos, decorated plates, and other curios sit on shelves in random spaces, along with stacks of cookbooks whose covers have turned tacky from decades of gas stove fumes. There is comfort in this particular kind of grit and clutter that attaches itself to rural self-built homes from the 1960s, away from the scrutiny of building codes and permits. The way lives and undusted objects expand to fill any available space.

Outside again, stepping back, the ad hoc-ness of the house reveals itself in other ways. Constructed over two decades of scavenged materials, its improvisatory style makes it difficult to determine where the true front of the structure lies. This quality makes it churn in memory and evade clear remembrance. It is a self-camouflaging blur—an architectural shift — softened at the edges by swishes of willow branches, a rutted gravel road, and folksy installations of found objects leaning against fence posts on the laneway to its door.

Although it is night — pitch blue-black with no streetlamps for miles — in the chilled-out April air, anyone who has lived in the area long enough can perceive the dense marsh on the Snye planning its annual crawl from the reservation toward town. Local white children with relatives who hunt ducks and fish are told that the floating mats of bulrushes, grasses, and cattails mark the legal boundary for gathering rights. If their boat drifts too far inward towards this buzzy wetland border, townie fishermen who have come to dip their hooks into the richer, luckier, river stock are asked to leave. Each year, retired grandfathers of Euro-Canadian descent can be found posted up on stools in the donut shop, mumbling paranoid thoughts to their coffee mug reflections: “Y’know, I think that rez over there is getting a little closer to town each year with all those rushes.” Island folks prefer to avoid sparking backlash in this small town, with its underbelly of tension and occasional violence towards most things Indigenous. Sometimes a verbal crosscheck emerges with a reminder: “This was all of ours once, before you arrived.” If you press your ear firmly against the ground this time of year, you can hear the crackling sound of seeds and insects pushing and popping their way up to the surface.

The table is in the house of a retired archeologist. An eccentric missing several fingers on one hand who, as a hobby, upcycles bones from roasted chickens into complicated sailing ships. In the mudroom where one enters, strings of drying animal bones hang from a workbench pegboard. The lingering smell of collagen and calcium incinerated by a Dremel tool, rasped leather, and airplane model glue permeate the room. Carcasses and hides in various states of processing could make it seem to those who didn't know better that they had stumbled into a backwoods horror film. Past the kitchen, on the fireplace mantel, a crumpled piece of tinfoil is used as a prop to backfill a story about a late-night call from the government in the 1980s to recover an alien craft that washed up on the shores of Lake Erie. Conspiracy theories and emergent folklore collide on this property, in a time more aligned with the Time-Life’s Mysteries of the Unknown encyclopedias and Unsolved Mysteries than Ancient Aliens.

Everything up until this point — though it may appear unsettling to outsiders — has been adopted into small town normalcy and legendry. Two of the people in the kitchen reside in the house, the other two are visitors. Weekend social callers. From tipped back chairs, things lean a little wine hazy, but aren't so muddled that the events of the night could be imagined. Above the table, there is another visitor — an injured crow that wandered onto the property, now recuperating in a cage hung at the ceiling in the corner next to the table. At first wary of visitors, she gradually begins to improvise around their conversation, adding top-end clicks and pops, guttural shuffling, and a low-beat throat rattle.

After dinner plates cleared, the crow begins to whistle. One of the guests remarks on the bad luck of the sound, it being night and all. An engrained teaching from her Métis Papa, who knew better than to tempt the attention of bad spirits attracted to breath forced between pursed lips after sundown, especially near the river. The crow whips itself into a frenzy, steam-kettling its displeasure and fanning her wings, clearly bored of caged convalescence.

A blast of beats resounds outside the kitchen window, a jump-scare written off as willow branches scraping by in the wind. Before the adrenaline can subside, a shadow forms in the corner underneath the cage. One of the guests senses it first, and then, wordless, without prompting, all four turn to watch it in unison, stuck in that strange and liminal space of shared ghost-time. The shadow manifests into a vaguely human-sized form, all swirling gray and black, opaque and dark at its core, but shimmering and transparent at the edges. It moves away from the corner and glides out of the kitchen, into the living room, and evaporates. Sudden silence from the crow amplifies the stuttered breath of humans, ringing in the ears.

The guests turn back, locking wide eyes, troubled by the consistency of the group encounter. No one needed to be told where to look, where to send their eyes to follow, or to describe what they’d just seen, other than to say collectively, “You just saw that, right?” The residents of the house, unphased, mention a rise in “visitations” since the corvid’s arrival. Visual manifestations of shadowy shapes, all centered around the cage. One of the hosts announces their eagerness to rewild the bird.

A weight lifts from the house when it is released a few days later, but the shadowy imprint remains for a month or so afterward, echoing along its usual path. There is a sensation that is difficult to describe attached to those moments when this memory resurfaces — a particular vibratory quality felt not just “in the bones,” as her mother would say while shudder-speaking: “someone walked over my future grave.” Rather, this memory is rooted in the eye. There is a desperation to recall in exacting detail the photographic quality of the landscape, the subterranean activities of the soil, up to the support beams under the kitchen floor, and each fleck of keratin dust floating through the air, cast off from splayed crow wings. The nearly-metaphysical sensation —a visceral and questioning-cold “wrongness” exudes from within the vitreous body, the optic nerve. A cellular-level haunting that repeats itself; a shadow skipping across an infinite fluttering loop.

Kristen Gallerneaux (Métis-Wendat) is a sound culture writer, artist, and museum curator based in Dearborn.

“Below Her”

By Manal Shoukair

Site specific installation; dimensions variable, nylon, solid bronze, 2022

Manal Shoukair is a Lebanese-American artist whose work in video performance, sculpture, and site-specific installations explore the complex intersectionality of her multicultural identity, Islamic spirituality, and contemporary femininity.

Non Compos Mentis (an excerpt)

By Rochelle Marrett

After the dream, all I can think of is decay.

I was standing in the kitchen with my mother waiting for the water to boil. Teabags already in our mugs; ginger to prepare the fasted stomach. Along with my persistent badgering and her recent blood sugar results, the mounting concerns (read: threats) of her primary care physician have led her to stop taking hers with sugar.

It was the morning after my return from the residency, and the day after the dream. The sky was still dark. I could see nothing through the windows, and secluded as I was in my own mind, I had very quickly forgotten even my mother’s presence. So, when she set her good hand on mine, splayed flat against the countertop, my eyes sprang wide, awakening from a trance. I could tell even she was startled by the unfamiliar contact. Her hand rested there a few beats, made two hesitant taps, then pulled away.

My mother’s love has never been demonstrably physical, or even verbal. Her love reveals itself in acts of service of indiscriminate scale. Off-hand, I may mention needing a new stapler or a set of notecards or needing to complete a nearly-expired return to an outlet store over an hour away, and before I can make the necessary arrangements, these issues will have been resolved. My mother likes to feel useful. She cannot believe that it is her mere presence that adorns my life.

Looking up, after the timid tap, I watched her face for an explanation, but her lips held tight. She reached for the kettle, cleared her throat, and began, hesitantly, to speak. She told me she was a fortune teller. I sighed. I was in no mood. I raised my cup and watched as she poured for us both. Unfazed by my tepid response, she forged on, scrunched her forehead, and gazed at something beyond my face. Then, with one hand cupped to an ear, she mumbled something inaudible. I played along. And in a voice tinged with revelation, she whispered, “They tell me you’re sinking, Zora,” and her eyes lanced mine. Despite my trying to hide it, she has discerned my sunken mood, knowing all too well there would be no lifting it. My moods changed willfully and of their own accord, and seemed indifferent, one way or the other, to external stimulation.

*

Here's the dream. I am stiff as a corpse watching as worms (or is it maggots?) burst through the skin on my arms and legs and I’m making desperate pleas for help to the people around me whose faces I do not recognize, but who stare on noncommittally, and then pitifully as though they can see no cause for concern, as though it were all in my own head and finally, helplessly, a scream, curdled in desperation, incites the maggots, blue, at first, now white, to rise up from behind my chest and burst from my mouth in astonishing numbers, and I’m choking, and they, the unfamiliar people who are now enclosing me entirely, beam in wonder, until one of them reaches out tentatively for my arm and before they can touch me, I shudder awake.

*

On my last day at the residency, moments after the dream, my mother called to tell me she had been held at gunpoint. I darted up in bed and before I could ask them, she answered all my questions. I’m fine, she said. Unharmed, she meant. I’m safe, I’m safe, she insisted. It seemed to take great effort. Zo, you should see it. FBI jackets everywhere. The bank is sending me home. Her tone implied it was the least they could do. Or maybe I was projecting. I didn’t give him the money. Her voice fell to a hush. I guess they’re happy about that. Then, she was quiet, so quiet I worried the call had dropped, and suddenly a fantastic array of horrific explanations sprung to mind. Slowly, she spoke again, drawing me back to reality. He was so young, Zo. And again, a pause. Seven thousand dollars? She was thinking aloud. So little, she said. So exact, she clarified. I agreed — it was an odd sum. It seemed to imply the money had already been allocated. What did he need it for? she mumbled, mournful. I sat silent, thinking of all her medical bills, out of sight, in the basket above the refrigerator.

Last summer, I had found her unconscious on the bathroom floor. The ambulance arrived within minutes. She’s suffered a stroke, the ER doctor informed me. And there was something striking about his use of the word suffered.

Slipped beneath bulletproof glass, the note had insisted, among other things, that she remain calm. It was itemized and hand-written on ruled notebook paper. And next to the final item, a meticulous heart had been drawn and colored in. I can say with certainty, that if the lid of my mind were to be knocked open ejecting all but five memories, the recollection of this note would be one of those remaining. It brought surprising tenderness to a notoriously callous interaction. And it was funny, in the way absurd things often are. I began to picture him drafting the note, (for use in his impending bank robbery — already an outrageous state of affairs). But then rereading it, and, finding himself dissatisfied with… the tone (?), choosing to pencil in a heart for good measure. Needless to say, the image endeared me to him. Although I had no way of corroborating its validity, and although he had threatened to shoot my mother.

I’ll call you when I get home, she said. And hung up. I love you, I said. To no one.

Rochelle Marrett is a Jamaican fiction writer and essayist currently at work on her first novel. Learn more and connect at rochellemarrett.com.

“Pregnant torso with head of the Pietà against mirror and sky,” 2021

By Kylie Lockwood

Archival inkjet print, 11 1/8" x 16 1/2". Courtesy of the artist and Simone DeSousa Gallery.

Kylie Lockwood (b. 1983, Detroit) is an interdisciplinary artist whose work reconciles the experience of living in a female body with the Western history of sculpture.

Out of the Fog

for adopted, fostered and trafficked people

By Katelyn Rivas

Here I am

Curly hair, Brown skin

Emerald golden sunflower eyes

Radicalized to the truth of my story

I am the lily in the valley

Determined to dance inside of darkness

I often felt like Loneliness was my name

Often I nursed my own wounds and bandaged my own wings

Despite being placed in the whitest countryside in America

Blackness still came for me

I was Black when my classmates did not want to stand next to

me in line for the recess bell

I was Black when I walked into the town’s beauty salon and

the hair stylist told me she was scared do my hair

But they did not own me despite the price tag beneath my

infant face

I get to be my version of Black

I love all of me and I am learning to be free and embrace my

audacious bravery

And that means, I can no longer go home. Not all the way.

Because there are men with rifles and confederate flags at

the gas station, their latest brown hide laying across their truck beds

Some might say that I have forgotten God

That every night I gather with other wild haired women in the

woods

To catch the stars

And who knows, maybe they are right?

Maybe I have found my ancestors in

places once marked forbidden, in the words that were blurred

out

There are women who have my back

And women behind them

And women behind them

All like me, searching and believing in something greater and

promised

Where there was no archive, the women carried in my body

cried out to me to be chosen

To be gathered up into a brilliant bouquet of spring flowers

To be held like the babies they never were allowed to be

I have looked for my first mother and found her

I have seen her in my dreams for decades

I have seen her in the mirror when brushing my teeth

I have seen her name on my official birth certificate

When I close my eyes, there she is

She is preparing dinner for all of my brothers and sisters

No longer are we separated

No longer displaced

No longer are we severed

The table is full and we ask for seconds

My mother calls me by my name.

My name is Love.

My name is Wanted.

My name is Belongs Here.

My name is Welcome Home.

Katelyn Rivas writes lyrical poetry about motherhood, transracial adoption, critical race theory, memory, and care for Black bodies.

“Division and Russel”

By Chris Turner

Acrylic on wood panel

For the past 25 years Chris Turner has been a working artist exhibiting in sculpture, painting, architectural design, and fabrication locally, nationally, and internationally while living and maintaining studios in Detroit.

Ode to Brown Child on an Airplane for the First Time

By Tariq Luthun

I don’t remember if I, too, was afraid,

but I do remember when the sky was

our thing — I could say the word: flight

and, in its stead, none would hear fight

spill from my jaw. The last time it took

a punch, I was in the boy’s bathroom,

surrounded — by boys — as a boy

unleashed his fist into me. I returned

the favor into his gut, and ran. Moments

before, he had called me gay, but I wasn’t

sure why I had to defend my glee — scarce

as it was. Hours later, a mess of tears

ran through me as I was pulled from gym

by the principal and suspended for defending

what little parts of myself I could still call

mine. I don’t know why this is the story

I choose to tell, but I do know that I may

forget it once we take off; shedding the skin

that everyone fears of releasing

towards the sun. Beautiful,

isn’t it, to be able to leave behind

this world, its lost and angry boys.

Tariq Luthun is a Detroit-born and Dearborn-raised poet, community organizer, and data engineer whose family hails from Gaza, Palestine.

“Get Yo Mans”

Sterling Toles

Acrylic on Canvas

Sterling Toles is a visual and sonic artist rooted in Detroit.