Lillien Waller x Christopher Jon Alexander

Four Ways of Looking at Christopher Jon Alexander

“Everything I’ve written is designed around behavior, so that it’s telling a story regardless of what we’re saying. So it’s still cinema.”

– Christopher Jon Alexander, 2016 Kresge Artist Fellow in Film

I’m sitting in Christopher Jon Alexander’s house, on a couch in his workspace. On this humid, late-July day, the filmmaker, performance artist and writer has generously turned off the small window AC unit so I can record our conversation—a work necessity that turns out to be a bit of a bust, anyway: this is real talk, and it is wide-ranging, enlightening and occasionally hilarious—but a good portion of it takes place in between cigarettes while we watch film footage for Alexander’s current project. Footage he is in, by the way, along with friends and collaborators Talese Harris, star of Alexander’s first film, A Complicated Cartoon, and four women known collectively as “the girls.”

The verbal sparring in this particular scene with three of the girls has chaotic rhythms, familiar to anybody who’s Black, broke or both while living in Detroit. It is argument but also play, a tease. A dance. Something a lot like love. But the scene is also a bit, a fictive construction created by Alexander in which the girls play out a tug-o-war with him over money, spontaneously creating characters for the camera.

The scene feels like documentary footage but is ultimately dramatic and sometimes absurd cinema verité. I tell him that it reminds me of French ethnographer and filmmaker Jean Rouch’s ethno-fiction, which attempted to capture the spontaneous “birth” of authentic action within defined fictional narratives. This scene, in which Alexander is both performing artist and maestro (unbeknownst to the viewer) is brilliant. And—based on the script he gave me to read a few days earlier—he is on to something. He has waited more than thirty years to have the creative chops to pull this off.

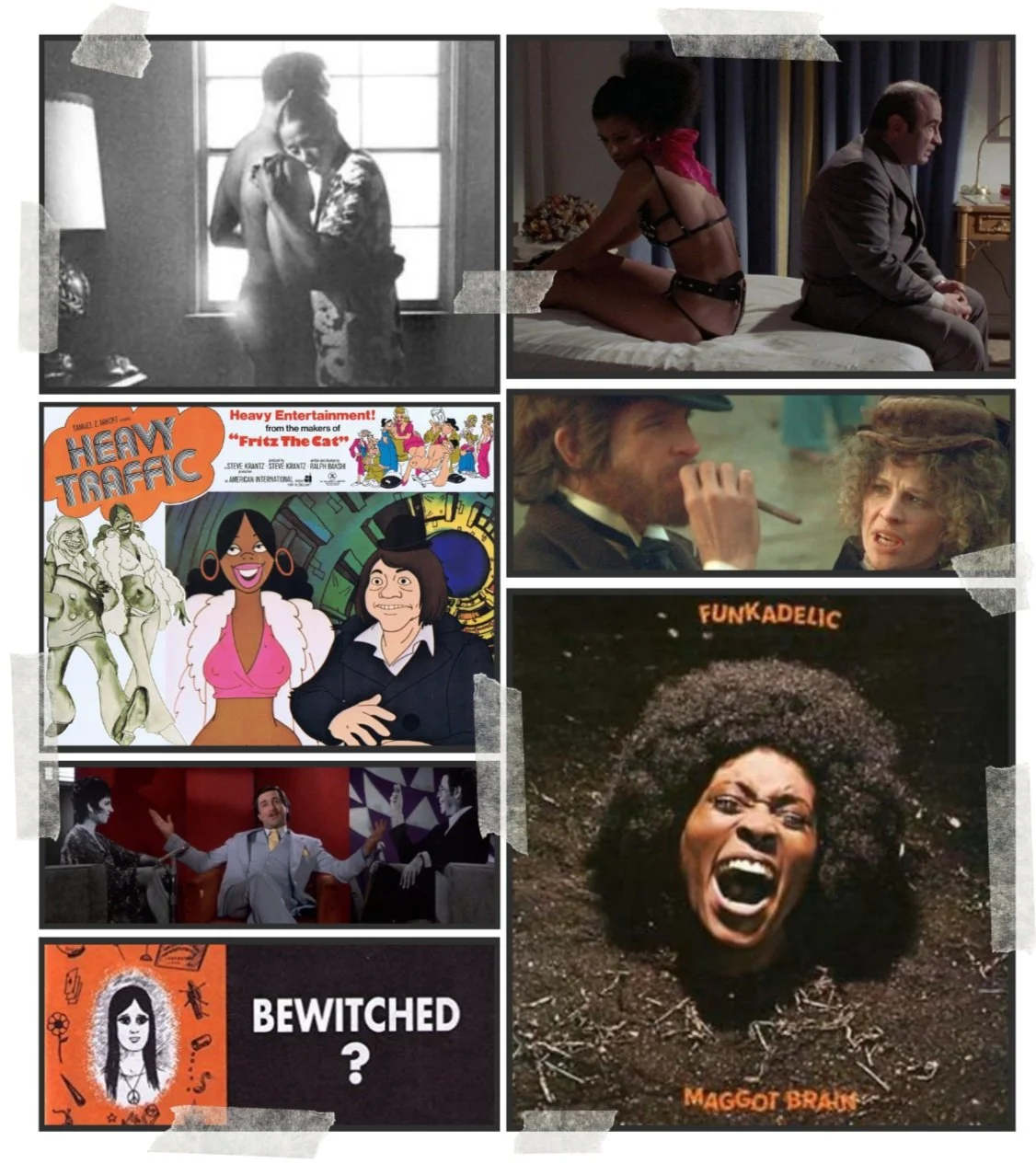

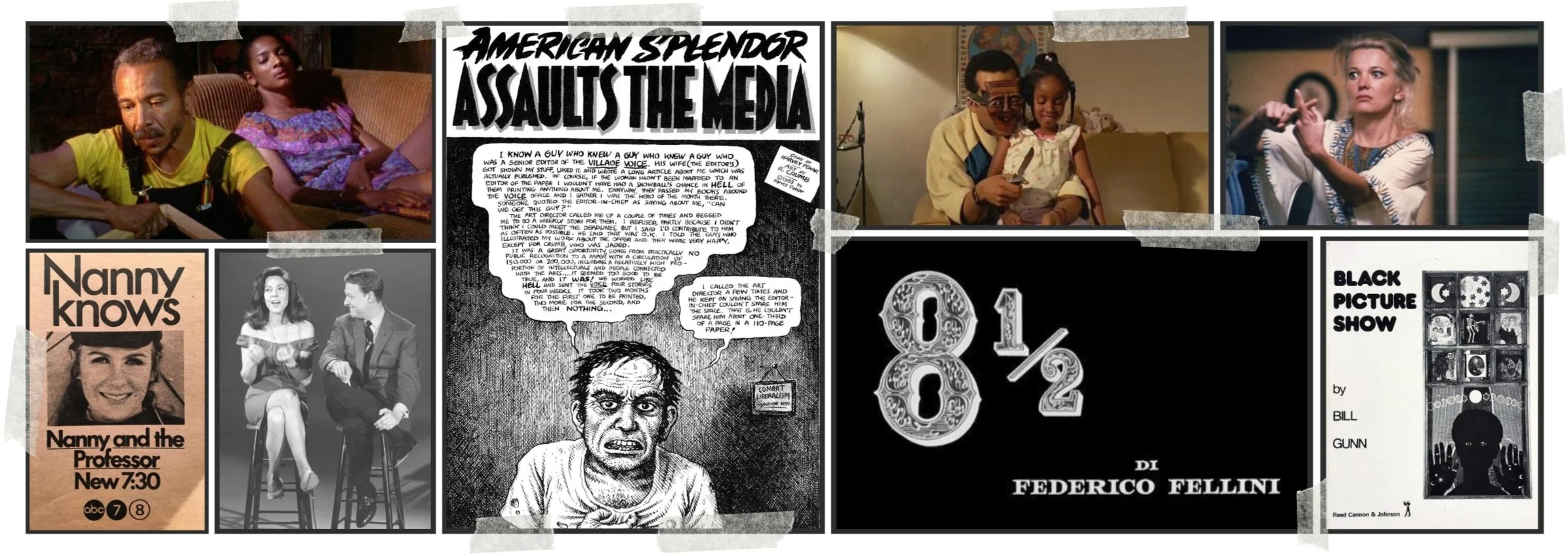

Images from Christopher Jon Alexander’s personal vision board of Black cultural production, global cinema, and mid-century American pop culture

Black Love uses new footage shot by Alexander on his laptop and his wife, Stephanie, on her cell phone; previously unscreened six-year-old footage of Alexander and the girls shot by Cass Corridor Films’ Oren Goldenberg in 2016; and selected clips from Alexander’s film Bible Stories. The script, according to Alexander, is less set-in-stone text than a series of performative “beats,” small units of moment-to-moment action in a scene—sometimes barely perceptible, like a shifting mood or motivation, or the discovery of new information—that move the story and its characters from here to there.

“What if I told you: who you are by the time we are finished, baby,” Stephanie says to Chris, “will be something altogether different?” Black Love is multiple films within a film moving, inexorably, from cynicism toward the miraculous.

What follows are a few key beats in the narrative of Chris Alexander’s transformed and transformational imagination—a sampling from his personal (and, you may not know it yet, but, uniquely Detroit) vision board of Black cultural production, global cinema and mid-century American pop culture—in his own words, “some Zwigoff’s Crumb meets Nanny and the Professor kinda shit.”

What the world needs is nuance.

It’s difficult to be more than one thing and Black simultaneously. “There is this lack of appreciation for nuance across the board, where everything has to be binary, you know? And I started examining what I was doing, and I realized that I don’t work from a place of intentional activism. But, what’s unintentionally activist about what I’m doing is my desire to expose the nuances of Black life without judgment.”

The whole casting thing doesn’t work.

The goal, Alexander points out, is to get characters to reveal themselves—to emerge—through people who, for all intents and purposes, are not actors. “When we casted for Bible stories, it was almost like I didn’t know these people well enough to know if they actually had the essence to pull this off,” he recalls. “I didn’t like that whole process. So, I think, since then, that’s what has made me flip the process to capture what I want to capture, to know the essence and to just make something with people I already know, where I know what I can get from them. A lot of the impetus for me wanting to make this is to capture some of that Black improvisational genius around me. Like Fine China [played by Molly in Black Love]. She was performing. She knew she was performing. And she was great.”

Images from Christopher Jon Alexander’s personal vision board of Black cultural production, global cinema, and mid-century American pop culture

Black people are great improvisers.

History actually tells us this, but the translation of generational survival skills into creative skills can be a seductive, mesmerizing thing to watch. Alexander appreciates improv as both: creative survival. “I grew up with Robert Altman films, right? And this guy, Ring Lardner, Jr., wrote the screenplay for M.A.S.H. for him,” Alexander says. “And what Altman did was, he threw it out and had everybody improvise to the beats. And it felt like, when you compared the television series M.A.S.H. to the movie—this is me as a kid deciphering this—the movie M.A.S.H. felt like a verb and that TV show felt like a noun. And what was going on was jazz-like improvisation. Now, if we could capture film in an Altman way, where it will still have this life, that’s the goal. That’s the challenge.”

What’s old is new again: the need for Black archetypes.

“AJ [Arthur Jafa] called me a Black Harvey Pekar,” Alexander says with both consternation and amusement. “Pekar got artists like [cartoonist/satirist] Robert Crumb to do these poetic vignettes from his life and put them in comic book form. In a sense, that’s what I’m doing with my own life. And there haven’t been a spectrum of archetypes for Black people in the mainstream. I have a friend who, when I refer to a situation—like me and him as Abbott and Costello—he objects with, ‘You always have to refer to white people when you’re making a point.’ But I’m not referring to white people. I’m referring to the archetypes that don’t exist for us to draw from, aesthetically. So the dream would be that, with whatever we do, we could create enough Black archetypes where that never has to happen again.”

Images from Christopher Jon Alexander’s personal vision board of Black cultural production, global cinema, and mid-century American pop culture

About the series:

Practice is a series of profiles that consider and amplify the distinctive voices of Kresge Artist Fellows. Each essay is the culmination of long-play conversations with Detroit artists who generously examine their own creative practices and who ask interesting questions of society, culture, and themselves.

About the author:

Detroit native Lillien Waller holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and degrees from University of Michigan, New School for Social Research, and Emory University. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Waller’s interdisciplinary work has been shown at Wasserman Projects in Detroit and as part of Wayne State University’s public art series In the Air II (2021–22). She has written on a range of topics—including contemporary visual art and design, modern art history, public policy, social justice issues, and American, Caribbean, and European studies—and profiled dozens of artists, scholars, and entrepreneurs. Waller is a Cave Canem Fellow (2001) and a Kresge Artist Fellow in Literary Arts (2015).