Lillien Waller x Cynthia Greig

Breath

When Cynthia Greig was ten years old, she was fitted with her first pair of glasses. She had probably needed them long before, she admits, but the experience of looking out of her window into the backyard while wearing her new glasses was transformative.

To think that the world and each small thing in it—which previously had seemed partially formed and fuzzy around the edges—could, in that moment, tender clarity.

“To see every leaf—the light hitting every leaf—and the detail I had been missing,” Greig explains. “I think the experience informed my work. Not right away, of course, but it has always been there. It’s about seeing more than you were capable of seeing before, more than what you see with your own eyes. That’s why cameras are so interesting to me. You make a picture with the camera, and then you look at the photograph, and there is always something there that you couldn’t see while you were looking through the viewfinder.”

Nebula (19 breaths), 2015, digital video loop

Greig’s body of work encompasses photography, filmmaking, video, and installation, a reflection of the many disciplines and vocations she has moved through to arrive here, now. Drawing offered her an early entrée, which led to printmaking and a lifelong interest in multiples—that is, multiplicity and what repetition reveals, the many ways something can exist or be understood.

Looking at her recent work, I wonder if the same applies to one’s own breath? What can we discover that a pandemic hasn’t already taught us about the precious, and fleeting, nature of breathing? Or is it, rather, not what breath is or does—an automatic reflex—but what it tells us about the passage of time?

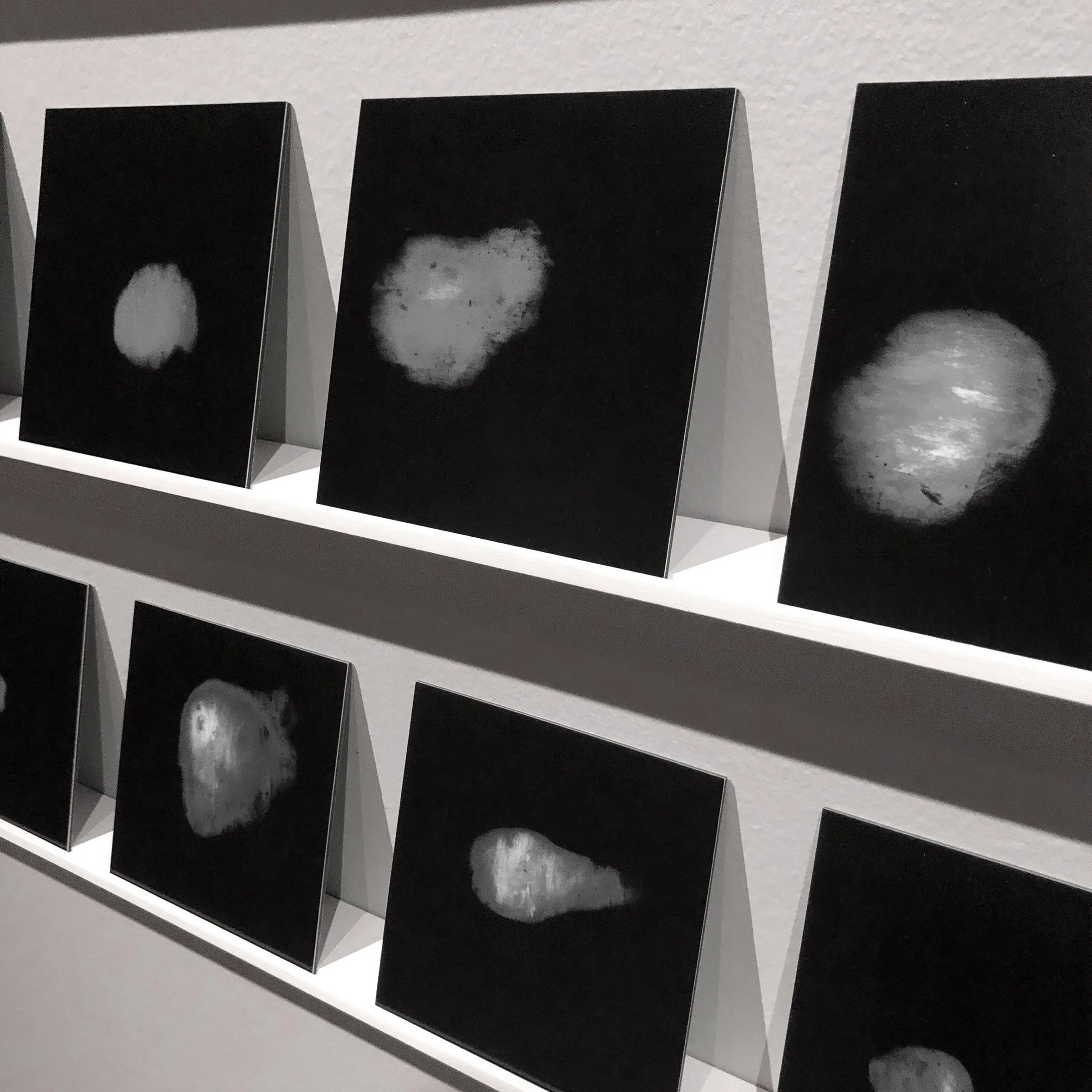

Greig has for some years been interested in how to visualize and memorialize breath. She first photographed various people breathing in the dark, their warm exhalations made visible by the colder atmosphere, but was dissatisfied with their similarity to clouds. Inspired by the crystallized “halos”—her own and others’—that appear on, and quickly disappear from, a cold window, she began creating her so-called breath portraits. Finally, and successfully, she began to use a scanner in various settings. The results were, as she puts it, “just about the breath. …There was this otherness about them. They’re breaths, yes, but what else are they? Something cosmological like nebulas, or like ultrasounds. I like hearing what other people see in them but it reminds me that’s the thing about abstraction: it’s really hard for humans not to label something that’s amorphous. You can see what you like—a constellation in the multiplicity and repetition. But it is breath.”

A number of Greig’s “Breath Scan Portraits” were included in the Breath Taking exhibit at the New Mexico Museum of Art in March 2021 and in October 2022 at Paul Kotula Projects in Ferndale, Michigan, in the group exhibition, Sleepwalker. Breath Taking had originally been planned for 2020 and took on a broader and more layered meaning a year later: in the wake of Covid, George Floyd—who died of asphyxiation at the hands of Minnesota police—and the Black Lives Matter protests of that summer, the rallying cry for which were Eric Garner’s last words “I can’t breathe.” (Garner had been killed by police in New York City in 2014.) Examining “the omnipresence of trauma and loss in America,” Sleepwalker showed Greig’s portraits in a related context, albeit more explicitly tuned to our individual experiences of mortality as well as a shared and perpetual experience of grief.

Left: Breath Scan Portraits, 2010-2020, 50 8x8 in. pigment prints mounted on Dibond, wood shelves, 62 in. x 108 in. Courtesy Paul Kotula Projects. Photo credit: P.D. Rearick.

Center: Breath Scan Portrait (Susan, printmaker, Grand Rapids, 56 years), 2012, pigment print mounted on Dibond, 8 x 8 in.

Right: Detail, Breath Scan Portraits, pigment prints mounted on Dibond, 8 x8 in. each. Photo credit: Jonathan Blaustein.

“I always think of breathing as the essence of ‘we are here,’” she says. “Think of a breath exhaled: the scanner captures the breath as it is disappearing. That breath as you see it in the image was never exactly there as you saw it because it was already fading away. To me, that’s a poetic metaphor for life. We’re here for a time and, eventually, we’re gone. It’s a reminder not be fearful and to embrace life while we’re here. I think the portraits are about movement and energy; they are also memento mori, but they are not mournful.”

Neither is Greig’s short, experimental film Black Box: This is not my Father (with Richard Smith, 2004). Greig wrote about the film’s impetus: “In 1990, my father and I travelled to the island of Culebra to document the after-effects of Hurricane Hugo. During this trip, he made plans for a future trip to Venezuela. This decisive moment ultimately led to the plane crash that ended his life.” The film includes a three-minute audio re-enactment of the flight’s black box transcript paired with two minutes of video footage Greig shot of her father during the trip to Culebra—the only moving images she has of him. The slow-motion images of her father with his friend loop, stutter and slowly distort. They are not paired with the audio in any strict sense; one does not reference the other. Rather, the audio, which is in untranslated Spanish, lends the otherwise joyful scene between two friends on a boat a sense of distance. The film’s subtitle, This is not my Father, becomes not only an ironic reference to the nature of images—which signal their subjects but exist only as representations—but also to the persistence, within all life, of its inevitable end.

Black Box, This is not my father, 2003, digital video loop

Greig’s work seems always to circle these concerns: the nature of life and death, grief and time. It observes and explores temporality—that is, the state or fact of being bound by time; that is, temporariness; that is, disappearance. It also evokes a sense of wonder.

At her core, Greig is a photographer, a seeker of souls. Her current project began in earnest when she moved up north, what Michiganders call every place that exists above Traverse City—in this case, Leelanau County. If you hold up your right hand, as we do, it’s the tip of the pinky finger. There, she returned to and began to photograph the abandoned structures she had first noticed on country drives with her aunt in the early 1970s. The shelters, plopped in the middle of old fields, housed migrant farm workers, mostly Mexicans. One bulb, one shelf, one window, one door: her historical research revealed that the structures—barracks—were organized systematically and offered each laborer the absolute minimum. Housing not homes. After all, if you have a bunk and a lamp, what role could beauty serve? Greig’s images conjure ghosts: not the restless chain-dragging movie variety but these are haunts nonetheless. The thing with ghosts, however, is that they won’t give up on life.

Left: Untitled no. 3, 2021, archival pigment print, 16 x 24 in. Right: Untitled no. 5, 2022, archival pigment print, 16 x 24 in.

“Photography is an imprint, a record. Painting is a kind of record. Sculpture is a record, too. But photography is a record in which the machine is a collaborator in that translation,” Greig says. “The camera becomes a filter between you and the image that you’ve made. Whatever you put in front of a camera, it was there. What you see may be a fragment, and may totally deceive you from the truth, but, before any kind of manipulation or intervention after the fact, whatever you see existed.”

About the series:

Practice is a series of profiles that consider and amplify the distinctive voices of Kresge Artist Fellows. Each essay is the culmination of long-play conversations with Detroit artists who generously examine their own creative practices and who ask interesting questions of society, culture, and themselves.

About the author:

Detroit native Lillien Waller holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and degrees from University of Michigan, New School for Social Research, and Emory University. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Waller’s interdisciplinary work has been shown at Wasserman Projects in Detroit and as part of Wayne State University’s public art series In the Air II (2021–22). She has written on a range of topics—including contemporary visual art and design, modern art history, public policy, social justice issues, and American, Caribbean, and European studies—and profiled dozens of artists, scholars, and entrepreneurs. Waller is a Cave Canem Fellow (2001) and a Kresge Artist Fellow in Literary Arts (2015).