Lillien Waller x Joan Kee

How to Draw Your Own Face

01

So much (of) art is about mortality.

Some would say that all art is about mortality: attempting to understand the inevitability, the truth of what life comes to—or hold it at bay. Art historian, critic, educator, and lawyer Joan Kee has been pondering this impermanence for some time in her own work, in caring for her parents as they age and, as it relates to this journey, in the perspective of viewers whose mortality and ability affect the way they see art.

“When we think about art, we just assume an upright viewer, someone who’s able to stand,” Kee says. “What are some of the assumptions that are embodied in that? It excludes people who are in wheelchairs, people who rely on mobility assistance equipment. People who are blind. One of the questions that my parents started me thinking about is: what are the effects of mortality on what it means to see, and be receptive to, scenes?”

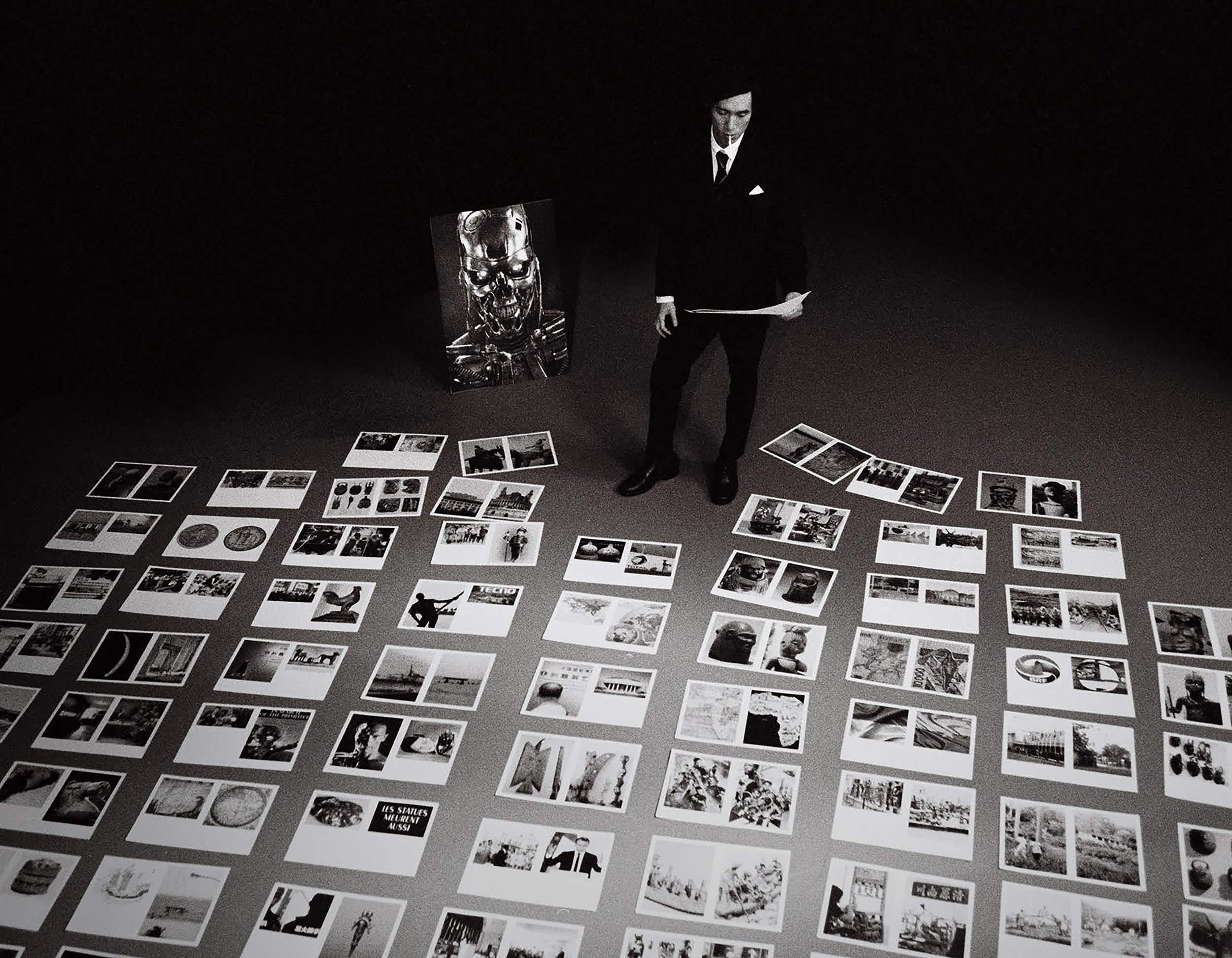

Left: Faith Ringgold, Feminist Series #14 of 20: Men of Eminence..., 1972/1993. Acrylic on canvas on framed fabric, 48x30”. © 2021 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Middle: Musquiqui Chihying, still from The Sculpture, 2018. Double-channel HD video, 22'10". Right: Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait. Series Emperor of Africa, SFEA 1949, 2013. Color print, dimensions variable. © Samuel Fosso, courtesy Jean Marc Patras / Paris.

02

Perhaps what I mean is a kind of immortality. What will become of us? What will come after us?

Kee’s writing on contemporary art seeks to illuminate the whole encounter, which, we discover, comprises other, discrete, encounters: artist and art, art and audience, identity and origin, past and future. Hers is a generous attitude toward scholarship and criticism but it’s also a humble one, rooted in the seemingly simple idea that art and the conversations around it should engage audiences beyond the academy. And neutrality is not an option. While in graduate school at New York University, Kee realized that “being exposed to all of these different backgrounds really forces you to account for your own subject position when you write about an artwork. You can’t be that neutral viewer, the reasonable person, the unqualified I, the unqualified third person. That’s not possible. Being in that kind of environment made me much more attuned to that.”

The result is that her explorations feel rigorous, thrilling even, and personal, I think to myself as I read “The Commons of Contemporary Southeast Asian Art.” This is a belief in a more equitable and expansive future beyond individual mortality and beyond art—even, and especially, if you and I might not be there to witness it. It’s what you leave for the use and benefit of others, as in her notion of “anticipatory art history.” Kee writes that “...an anticipatory art history stresses a vision of history that reconfigures itself as a new mythology better able to produce ethically and politically aware audiences. It requires prioritising a truthfully imagined future over misleading revisions of the past.”

03

It’s really an expression of anxiety or peril: a sense of endangerment.

Kee practices such anticipatory art history in For Asian Lives to Matter (Artforum, May 2021), her examination of Chinese-American Chao-Chen Yang’s photograph, Apprehension (c. 1942). Yang was a diplomat in the nationalist government of Chiang-Kai-shek during World War II and eventually became a film photographer. His photo captures a young Asian man’s face in extreme close-up, emerging from shadow but held in an eerie orange glow clutching a phone receiver. The image is one of panic, slight confusion, and, as Kee points out: “…Yang suffuses Apprehension with film-noir performativity. Behold the moment when the hero—or suspect—is wakened at an ungodly hour by a shrilly ringing telephone. Bare-chested, he presses the receiver to his ear, and the camera reciprocates in turn, moving so close to his face that it looks thrust into the lens.”

Kee follows the orange light inside Apprehension, likening it to the strange and singular glow of artillery fire in Gu Yuan’s woodblock print of Mao Zedong’s troops during the Chinese Civil War, The Bridge of People (1948). It’s a bit of a leap, she admits (more of a hop), as Yang and Gu Yuan were on opposite sides during that war. But such speculative moves enlarge our experience of the image, as when Kee imagines that what the man in the photo hears on the other end of the line is the voice of Korean-American artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, who was raped and murdered in New York City in 1982.

Let’s not pretend, Kee seems to say, that the fear of harm (the apprehension) in this image can be viewed outside the broader context of that era’s fear of a “yellow peril”—and this one’s. But who’s in peril here? Kee wrote and published this essay during the second surge of the Covid-19 pandemic—and all the anti-Asian racism that accompanied it—and a few months after the murders of six Asian women in a mass shooting in Atlanta.

“The resonance is strong enough,” Kee writes of her speculations, “to warrant asking whether Asian bodies are visible only in the light of emergency: whirling flashers, raging infernos, the hellfire of bombs, even the overhead glare of an interrogation cell.”

Left: Chao-Chen Yang, Apprehension, c. 1942. Photograph, 16x12.5”. Collection of Edgar Yang. Right: Cover of Geometries of Afro Asia: Art beyond Solidarity, forthcoming April 2023 from the University of California Press. For more information about the cover image, visit bit.ly/3N3ej3P

04

What I really mean is time. All art is definitely about time.

The child of immigrants, Kee attended Yale as an undergraduate, and there were three courses her father insisted she take. Astronomy would serve to remind her of her own insignificance. “I was forced to think about how it is that we exist for just a brief moment in the world.” Another course was drawing, taken in part because her mother had trained as an artist. “She always told me that there was nothing more difficult than to draw your own face,” Kee recalls. “Although the physical likeness might be there, the image will seem completely drained of life when you finish it. I’m still struck by that idea of perennial incompletion, a goal you’ll never be able to reach.”

“What is it that you cannot describe?” Every class centered around a particular word or set of phrases, Kee says of her first art history course. It was the third her father insisted she take. And this was the question her professor emphasized most. The course was a survey on African American art—one of the few such university courses offered in the United States in the mid-90s—and it was taught by African American art historian Judith Wilson. Kee explains that Wilson’s emphasis on this question was among the lessons she learned in that course that resonate today in her own work. “Even though every class would begin with ‘What is this? What color is it? What shape is it?’ there would always come a point where the words started to fail. There was a lesson in humility there, and that was one of the main turning points for me.”

Joan Kee is the author of Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method (2013) and Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Post-Sixties America (2019). Her third book, The Geometries of Afro Asia: Art Beyond Solidarity, is forthcoming.

About the series:

Practice is a series of profiles that consider and amplify the distinctive voices of Kresge Artist Fellows. Each essay is the culmination of long-play conversations with Detroit artists who generously examine their own creative practices and who ask interesting questions of society, culture, and themselves.

About the author:

Detroit native Lillien Waller holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and degrees from University of Michigan, New School for Social Research, and Emory University. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Waller’s interdisciplinary work has been shown at Wasserman Projects in Detroit and as part of Wayne State University’s public art series In the Air II (2021–22). She has written on a range of topics—including contemporary visual art and design, modern art history, public policy, social justice issues, and American, Caribbean, and European studies—and profiled dozens of artists, scholars, and entrepreneurs. Waller is a Cave Canem Fellow (2001) and a Kresge Artist Fellow in Literary Arts (2015).