Lillien Waller x Neha Vedpathak

Once Said

Toward the beginning of her career, painter and interdisciplinary artist Neha Vedpathak began to experiment with so-called masses, handmade mounds made of materials culled from nature across multiple landscapes: soil from Chicago, grasses from France, and snow from Colorado. The mounds are little interventions in what appear to be serene topographies, living installations that are both catalyst and evidence and—according to Vedpathak—none are extant except the soil mounds. The others survive primarily in the photos the artist took of them and in the memories of whomever had the opportunity to experience them in person.

Snowmass, 2010, Snow, turmeric, kumkum, Variable

The mounds feel like first attempts at language, literally and figuratively emergent—a way for Vedpathak to connect to the environment, to herself, to ritual, and to the past. She began the work in 2010, a crucial time both personally and professionally, while in residence at Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass Village, Colorado. That year was the first time she fully allowed her own heritage—she was born and raised in Pune, India—to enter her work with intention, as in the small gestures of turmeric and kumkum powders that dot the mounds in the Snowmass installation. They were among the pigments she always carried around; she used them to create more visible contrast against the white snow. She realized during that time that it had been nearly four years since she had returned to India. She was not only an Indian artist but also “an Indian artist abroad,” and it was the first time she had dared to refer to herself as an artist at all. It was “a door cracking open,” she recalls, a fertile time creatively and, given her distance from extended family, she was not going to squander the opportunity.

“I was allowing my body and my hand and my materials to guide me,” Vedpathak says. “What implications does this have? How does it complicate other aspects of the work—making work and showing work and talking about work?”

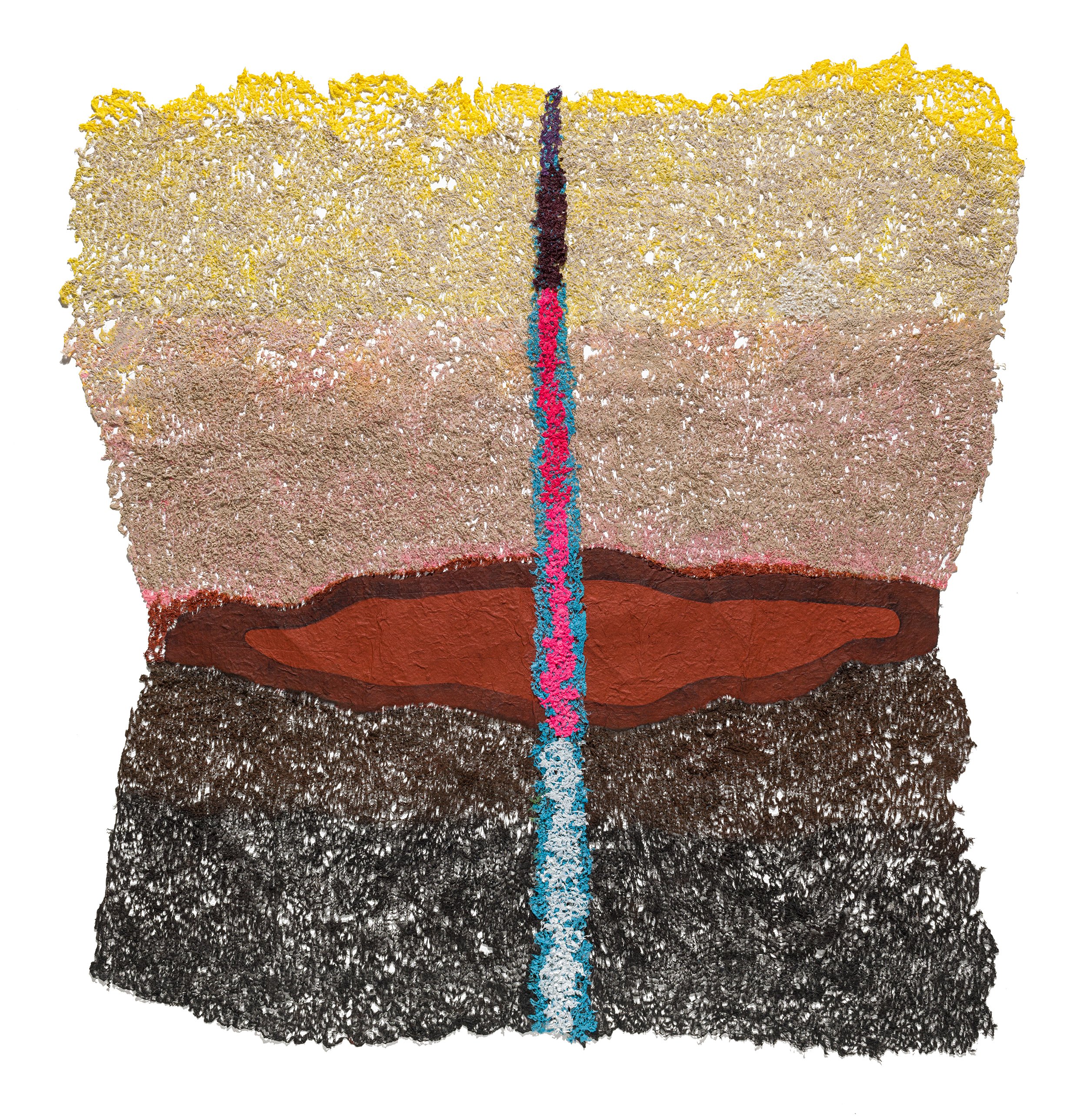

Vedpathak is very clear that language, as such, is not an overriding concern in her work, even as communicating with her audience is. Since at least 2009, she has integrated paper into her paintings and other works and, for several years now, she has created small- and large-scale installations, paintings, and sculptures with handmade Japanese paper. Using a technique she developed called “plucking,” Vedpathak spends hundreds of hours using small pins to pluck papers—methodically separating and individuating their fibers—creating a lacework texture. The plucked pieces, closely resembling textiles, are then further manipulated with paint, sewing, and other techniques and ultimately deployed as individual artworks.

Left: Continuum 3 (Golden Nectar), 2022, Hand plucked Japanese paper, acrylic paint, thread, 35x31 in.

Center: Equanimity, 2023, Hand plucked Japanese paper, acrylic paint, thread, 40x38 in.

Right: Sex, 2022, Hand plucked Japanese paper, acrylic paint, thread, 63x49 in.

The meditative aspect of Vedpathak’s practice is apparent. What may not necessarily be apparent is that she has in a certain sense created language—a ritualized and systematic, yet informal, mode of communication. Is that what art is? Is that what it should be? This thought came to mind while attending the artist’s recent show, Creative Force (April 22–May 27, 2023) at the David Klein Gallery in Detroit. Speaking on her current practice as a whole, Vedpathak notes, “My [aesthetic] language is still abstract, and I’m not a narrative artist in many ways. Yet, I’m going to say and express a lot. I have a lot of things to say through my work.”

The Creative Force exhibit did just that: Tantric and Zen philosophy; the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade and the artist’s need to understand and contextualize her own anger and confusion; society’s fear of women’s power, sexuality and self-determination. It was all there, but not in any way that could be considered literal or pedantic.

“Through my work, I want to be very efficient. My hope is that it still reaches people,” Vedpathak explains. “It’s a very demanding thing on the work and the audience and myself. I love to say nothing,” she says, smiling, “and for everything to be understood. That’s where my deepest, happiest, most satisfied self lives.

“Some aspects of you are your core self, who you are. And then others…” Her voice trails off for a moment. “I think about the idea of Sufism, where the truth once said becomes untrue. I think there’s something to that. We don’t always need words. I think that for art it is literally that: the work should be able to say so much more than I am capable of saying.”

Vedpathak uses the example of being moved to tears in the presence of a small drawing that was made fifty years before she was born. A language without words? Absolutely. It’s not a hard thing to imagine, even in our age of information bombardment, density and—often—deceptiveness. And, such a language has of course already existed, many times over and across the globe, as art and as artifact. With relation to Vedpathak’s plucked paper sculptures, that take on a unique fabric-like texture and vibrancy, Incan quipu immediately come to mind: a sophisticated system of color-coded knotted ropes that are believed to contain information from cultural stories, histories, accounting systems, and much more. They are also, even to an untutored eye, beautiful.

Top: Untitled, 2010, Hand plucked Japanese paper, Variable

Bottom: Breathing Spaces-II, 2010, Hand plucked Japanese paper, tumeric, kumkum, mirrors, Variable

Vedpathak’s work is as much about what is felt and derived from the encounter as it is about ideas, philosophy or our current political moment.

“The energy of that mark making,” Vedpathak says, “when it hits the right frequency, when both of us [artist and audience] are in the same zone, ‘magic’ happens. That is why plucking is so special to me: there is an inherent energy that I put in it. With the painting and sewing and intentionality behind it, when it comes to the surface, it’s not going to hit everyone the same way. But there is something in there for people to engage with, if and when they’re ready. There are some truths in life that can be expressed through art that probably cannot be expressed any other way.”

About the series:

Practice is a series of profiles that consider and amplify the distinctive voices of Kresge Artist Fellows. Each essay is the culmination of long-play conversations with Detroit artists who generously examine their own creative practices and who ask interesting questions of society, culture, and themselves.

About the author:

Detroit native Lillien Waller holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and degrees from University of Michigan, New School for Social Research, and Emory University. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Waller’s interdisciplinary work has been shown at Wasserman Projects in Detroit and as part of Wayne State University’s public art series In the Air II (2021–22). She has written on a range of topics—including contemporary visual art and design, modern art history, public policy, social justice issues, and American, Caribbean, and European studies—and profiled dozens of artists, scholars, and entrepreneurs. Waller is a Cave Canem Fellow (2001) and a Kresge Artist Fellow in Literary Arts (2015).