Lillien Waller x Ann Eskridge

Becoming Visible

There’s a moment in 2021 Kresge Artist Fellow Ann Eskridge’s play If Pekin is a Duck, Why am I in Chicago? when the characters Soldier Boy and Dupree are sitting in the Pekin Theatre bar, drinking and waiting, and Dupree asks Soldier Boy a seemingly innocuous question. The year is 1918, but for African American men, the war is not over.

DUPREE

So, Soldier Boy, what’s your real name?SOLDIER BOY

Why?DUPREE

‘cause I wanna know who I’m talkin’ to.SOLDIER BOY

Does it matter? Didn’t matter to my sergeant.

He kept calling me boy…or hey you…or Soldier Boy.

The conversation turns. Soldier Boy won’t give straight answers and Dupree won’t stop pummeling him with questions: What’s your real name? Where in France did you serve? What division? Did you see any action? Big Man, who is also in the room, attempts to lower the escalating tension. He’s got plans and this back-and-forth is an unwelcome distraction. Finally, Soldier Boy relents. No one is prepared for his revelation.

If Pekin is a Duck, Why Am I in Chicago? Playbook

Soldier Boy pulls out a gun and slams it on the table. Big Man and Dupree freeze. Through this dialogue, Soldier Boy carelessly waves the gun around.

SOLDIER BOY (breaking down)

He was my friend, my best friend. I saw him get his head blown off…and…and wasn’t nothin’ I could do about it. I stayed with him, even when I knew there was no hope. I prayed I’d die, too, but all I got was this.…

Wasn’t no fancy nightclubs and theaters for Casey. Wasn’t no blondes and whiskey to celebrate with. Wasn’t no Taps for him when he died. Ain’t have no head. Give him my tags…

…then I walked away. To the military, it’s Argos Smalls from Okatie, South Carolina, they buried in that hole. Argos Smalls a ghost.

…

You wanna know my name? Call me Casey. That was his.

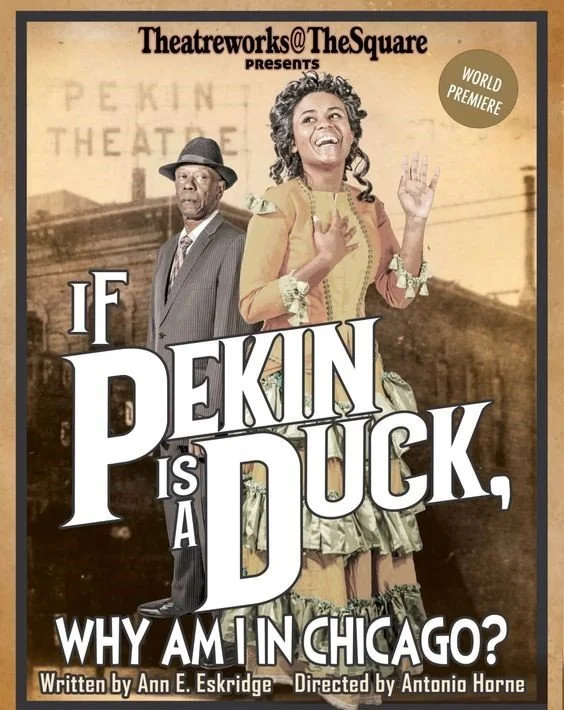

It’s a pivotal scene that changes so much of what is emotionally at stake in the piece. In another room, composer Joe Jordan and lyricist Alfred “Alf” Anderson (Eskridge’s fictionalized versions of historical figures) attempt to write a song in one hour. They have been kidnapped and brought to the Pekin by Big Man—a gangster who believes that if the duo can just write a great song, he can win a bet and buy back and restore Chicago’s first Black musical theatre.

But in the exchange between Dupree and Soldier Boy—and, later, in the exchanges between Joe and Alf—we begin to see these characters for who they really are. They become fully visible to us in spite of their clever nicknames and lyrical banter. We begin to see the writer Ann Eskridge more clearly, too, in full creative bloom for this, her first produced feature-length play after more than thirty years of writing screenplays and works for the theatre. Directed by Antonio Horne, If Pekin is a Duck, Why am I in Chicago? had its world premiere in January 2023 at TheatreWorks @ The Square in Memphis, Tennessee.

The story of If Pekin is a Duck, while fictional, is inspired by historical fact—both within the play’s narrative and Eskridge’s own childhood on the south side of Chicago. It’s what I’m realizing is a typical Ann Eskridge story in which accident, luck, talent and sheer will combine, all within a frame of near-forgotten Black cultural life. No living person remembers this era and these figures, a reality that lends Eskridge’s play a sense of urgency.

Left: Uncle Alf and Aunt Hazel; Center: Pekin Theatre, Chicago, Illinois; Right: Momma, Aunt Hazel, and Ann

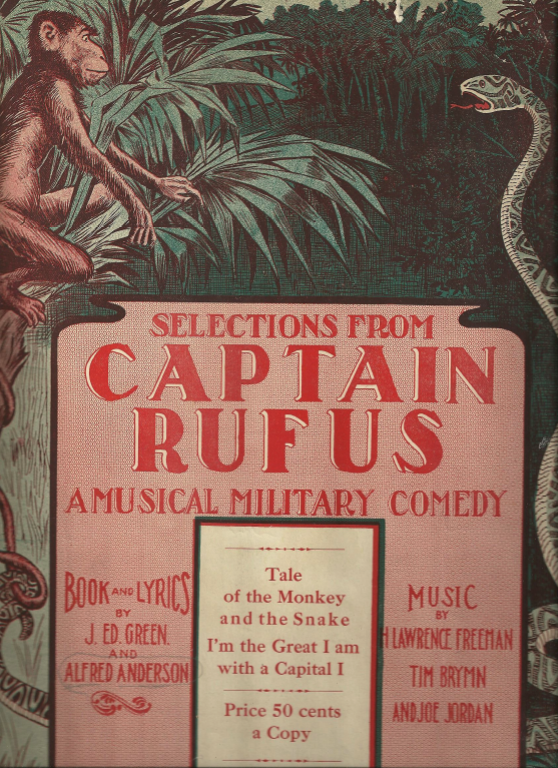

“He was a family friend. He actually lived below my mother and grandmother when they lived on Langley. And his name was Alfred Anderson. He was a lyricist and a poet,” Eskridge explains. “Aunt Hazel was his wife and she was a good friend of my family. But when Hazel died, we got some of her stuff. And then when my dad died, I got some of his stuff and Uncle Alf’s stuff, we’re talking from before the turn of the century, 1899. There were these “coon” songs that he wrote,”—a term used to describe white and, eventually, Black 19th- and 20th-century minstrel music from which ragtime evolved—“and I had them in a box and I put them in the closet. And then I took a musical theater class. And I said, ‘Oh, okay. I could use some of Uncle Alf’s stuff.’”

Eskridge’s research led her to Anderson’s collaborators, a who’s who of early 20th century African American song, including Joe Jordan who was the musical director of the real-life Pekin Theatre and is depicted in the play. “I said, ‘I have a story,’” Eskridge explains.

Eskridge’s creative writing success has been a long time coming although, technically, it has already come. Multiple times. But fate always moved in another direction. Throughout it all, however, she wrote.

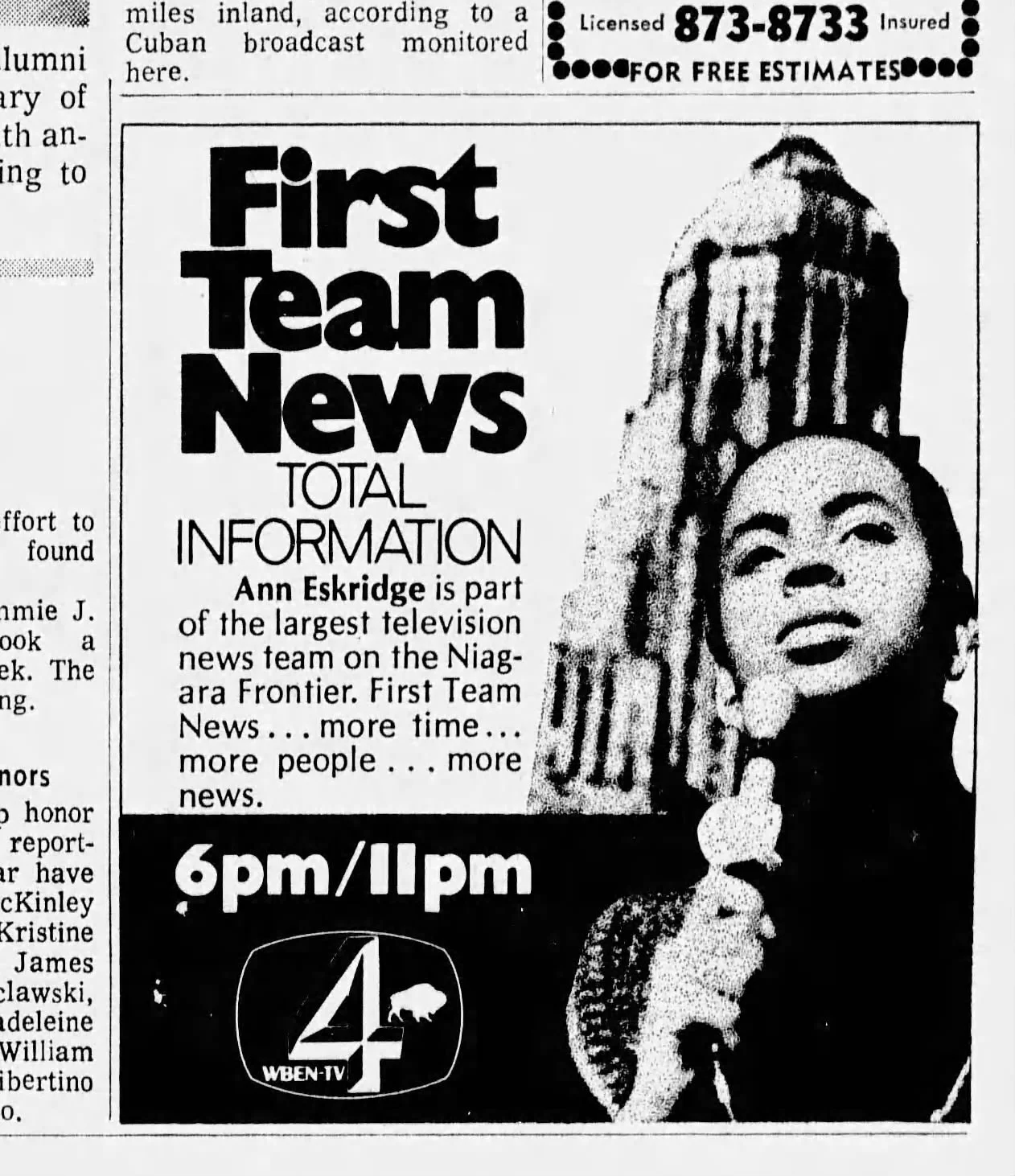

Eskridge built a thirty-year career in broadcast journalism, public relations, state politics and teaching, which began while she was still a junior at the University of Oklahoma. She would go on to become the first Black woman graduate of what is now known as the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

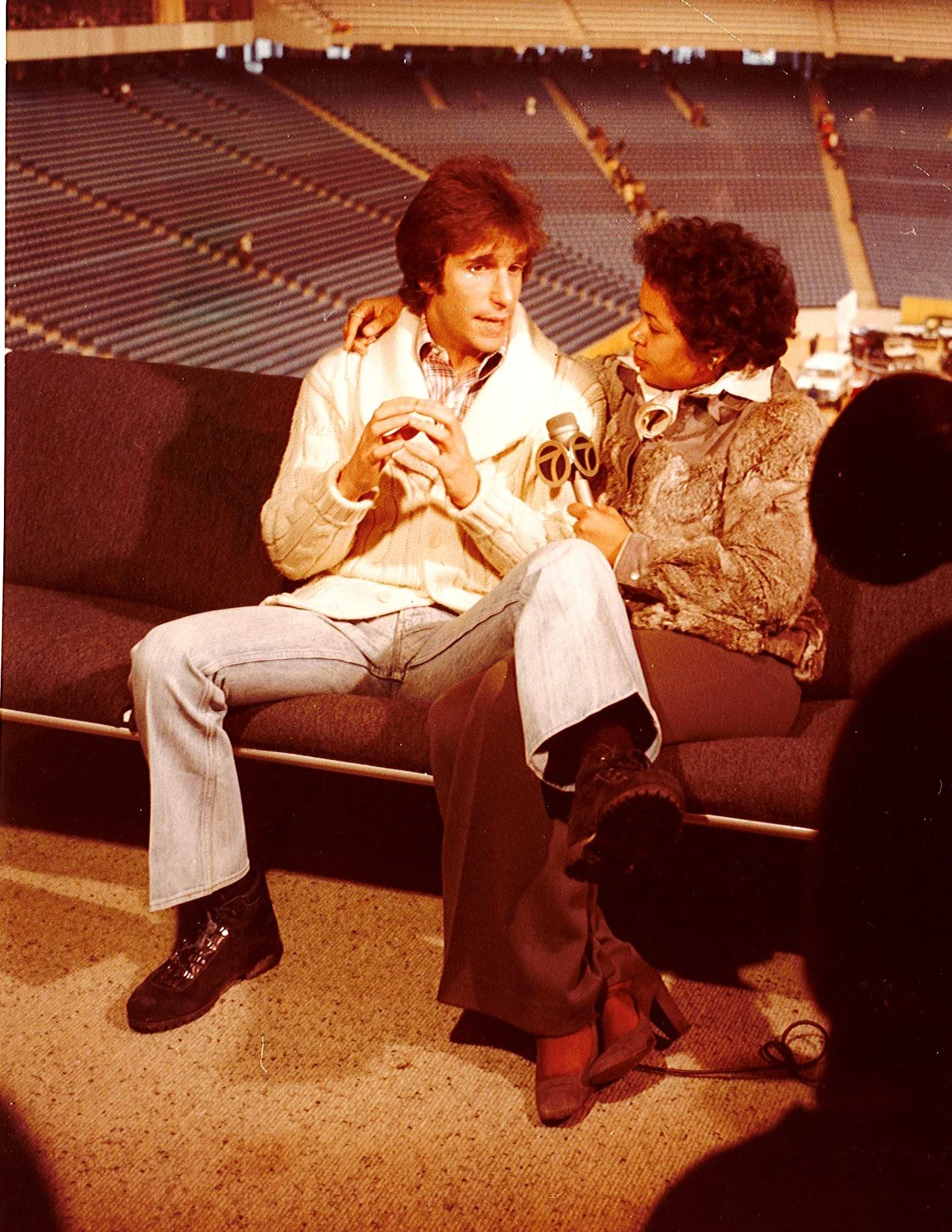

Eskridge’s media career would lead her to Buffalo—where, three weeks into her new role, she was sent to cover the Attica prison uprising—and, ultimately, to Detroit, where she covered feature stories for WXYZ. She was assigned a lot of sports features, even though she didn’t care about sports. After journalism, she pulled a five-year stint in state government in the Republican Milliken administration. She didn’t care about politics, either. But she did care about writing creatively.

At Golightly Education Center, she was invited to develop a program in mass media. “Teaching others actually taught me how to be a better person, how to be able to see a future for kids who couldn’t see it for themselves. I am so proud of the students that I had at Golightly,” Eskridge says. “I mean, one [former student] is an inspirational talk show host. I also taught scriptwriting for a brief period for Inside/Out after I left Golightly. One of my students was Michael R. Jackson, the Tony Award and 2020 Pulitzer Prize winner for A Strange Loop. He told me that I was the first one to teach him scriptwriting. Two more are writers. They’re all interesting. They’re all thinkers. They’re intuitive, they’re creative. They’re fabulous people.”

Teaching re-ignited Eskridge’s passion for her own stories, Black stories. And because of her eight-year stint in broadcast journalism, she understood the relationship between the camera and what it sees. She began to write screenplays, the first of which was The Sanctuary, the story of a real-life woman in the West Grand Boulevard-area of Detroit who spent ten years building a large, and controversial, altar to honor the spirits of the dead. Is it art or is it an eyesore?

Left: Ann as a reporter in Buffalo at WBEN-TV. Center: Ann interviewing Henry Winkler for WXYZ-TV in Detroit. Right: Ann with Lt. Governor James Damman.

The screenplay was accepted into a workshop at the American Film Institute. Then it was optioned by Sundance, which eventually passed. But her screenplay The Kangol Kid and the Eight Ball Nightmare was accepted, then produced, by Wonderworks, a PBS anthology series. It aired under the title Brother Future, about a Black teenager from Detroit who gets hit by a car and knocked unconscious into South Carolina in 1822 where everyone thinks he’s a runaway slave. Years later, The Sanctuary was also one of only two scripts chosen for staged readings at The Growing Stage in New Jersey.

She uses these feast and famine experiences as a way of placing her play- and screenwriting journey—and, indeed, the life of most artists—in context.

“American Film Institute, boom! Sundance, boom! Warner Brothers Comedy Development Program, boom! Brother Future for PBS, boom! Then nothing major for thirty years, and Purple Rose wants to commission me to do something. Okay, fine. Growing Stages is interested in The Sanctuary, great. But in the thirty years in-between, I kept on writing.

“Sometimes it doesn’t happen when you want it to happen,” she continues. “I went to the premiere of If Pekin is a Duck with my niece, and it was fabulous. Except for short pieces, this was my first time seeing a feature-length play that I had written in full costume, full performance. And they sang and they danced, and I was the one who wrote the ‘winning song.’

“And by the time the cast performed it, the audience started clapping along and I went, ‘Yeah.’”

About the series:

Practice is a series of profiles that consider and amplify the distinctive voices of Kresge Artist Fellows. Each essay is the culmination of long-play conversations with Detroit artists who generously examine their own creative practices and who ask interesting questions of society, culture, and themselves.

About the author:

Detroit native Lillien Waller holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and degrees from University of Michigan, New School for Social Research, and Emory University. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets, and she is editor of the anthology American Ghost: Poets on Life after Industry (Stockport Flats). Waller’s interdisciplinary work has been shown at Wasserman Projects in Detroit and as part of Wayne State University’s public art series In the Air II (2021–22). She has written on a range of topics—including contemporary visual art and design, modern art history, public policy, social justice issues, and American, Caribbean, and European studies—and profiled dozens of artists, scholars, and entrepreneurs. Waller is a Cave Canem Fellow (2001) and a Kresge Artist Fellow in Literary Arts (2015).